Editor’s note: The following Q&A has been adapted from TANGRAM Volume Two for Journal of Play.

Eleven years ago, I saw John Edmark transform a pinecone into a helix with the flick of his wrist. A sharp twirl in the other direction, and the metamorphosis was reversed. The shape shift didn’t happen all at once but rather one layer at a time—like a split-flap display board at a train station going click, click, click.

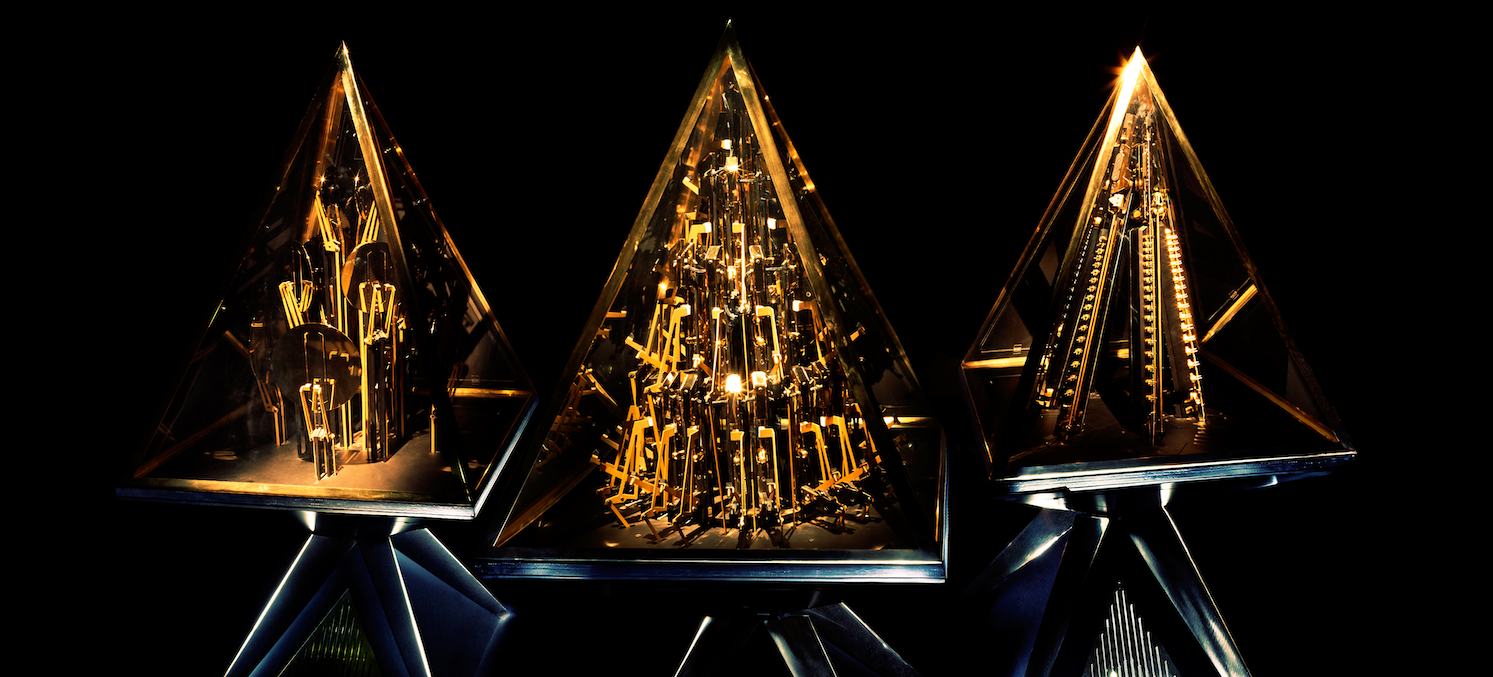

Creating wonders inspired by nature is exactly what makes Edmark’s work so profound. Among his marvels are a number of kinetic sculptures known as “Blooms” that, when spun under strobe lights, animate outward ad infinitum.

The long-time spiral enthusiast has been teaching mechanical engineering and design at Stanford University for almost twenty years. His unique artwork has been featured in prestigious museums, national newspapers, and on popular television programs around the world. Clips of his sculptures have racked up millions of views on YouTube.

We caught up with the artist to learn how he uses the golden ratio in a radial manner to produce particular forms and behaviors determined by unique parametric seeds that boggle the mind.

Art of Play: I want to talk a little bit about physical spaces versus digital spaces and how your journey has vacillated between the two. When you were a kid, were you drawn to computers first and coding, or were you drawn to physical making of objects?

John Edmark: When I was a kid, personal computers weren’t available. I was very much focused on making stuff in the real world. I spent endless hours with Legos—even past the age where it felt appropriate. I remember being a little bit embarrassed about still enjoying Lego at the age of 14, but I did. I also enjoyed building treehouses and rafts.

As an adult, I worked in computer graphics and virtual environments research at Bell Labs for a number of years. I eventually became disenchanted with always making things in the virtual world. I missed the constraints that one deals with when working in the physical world, and the dialogue you have with materials and tools and hardware that is sort of non-existent in the virtual world.

Making an object in the real world that does something unexpected is more mystifying and delightful than something created in the digital world because computers are so sophisticated. The way many people view computer technology is that it can do anything. So, in some sense, there’s nothing a computer can do that’s truly surprising.

It’s just like, “Well, yeah, somebody spent enough time programming and they got it to do that.” But to experience something physical that appears to be doing the impossible is to be astonished and have your understanding of the world challenged in a delightful way. Creating objects capable of evoking such a response is the ambition—rarely achieved—of much of my work.

It’s funny that you mentioned how surprising things can be in the physical world, because I think that’s incredibly applicable to the natural world.

Look at what Mother Nature manages to do by combining the fundamental building blocks of atoms and molecules in myriad ways to create such remarkable constructions and mechanical behaviors. ... It’s just mind-boggling, and it’s all real.

There’s a power to being in nature, whether it be a forest or a garden. I’m not metaphysically inclined, but it’s impacting me in a way that I cannot deny. I don’t know the mechanism. I don’t know why it has this effect on me, but I think part of the equation has to do with being in the presence of the ongoing miracle of self-developing structures and animated beings that are able to reproduce themselves and evolve over time. It’s awe-inspiring. But that doesn’t really explain the profound sense of peace I often experience in those places.

One of those mind-boggling building blocks that you have explored in your work is the golden ratio?

[Originally] I began exploring logarithmic spirals, which I found to be quite intriguing. ... It’s the shape you might think of as a snail or nautilus shell. They have a beautiful kind of symmetry, but not a mirror symmetry. It’s lopsided, in a sense.

For various reasons, I wanted to make spiral patterns that were a little more balanced. In my attempt to find a solution, I became aware of how nature was solving the same problem using the golden ratio in angular form. The way a plant grows leaves around a stem or petals around a bud—the system is incredibly simple but profound. This results in highly balanced radial patterns. So, I started to use the same method in my spiral explorations.

At some point, I realized that if you take a perfectly formed pinecone, artichoke, or pineapple, and you spin it under a strobe light flashing every 137.5 degrees, this naturally formed object becomes an animated sculpture. Now, that was both a discovery and invention. No, actually, I don’t know what it was. Because nature doesn’t make these things to be spun under strobe lights, but they’ve had that potential since time immemorial; and nature did invent the system that makes it possible for them to become animated sculptures. I had seen this kind of behavior appear in my own work quite unexpectedly, but I must sheepishly admit that it took me five years to realize: “Oh, wow, okay. I can actually make something that will do that on purpose.”

And when you made the first bloom, where did you take inspiration for that form?

My first “Bloom” was a spherical form arrayed with simple finger-like appendages that grew out from the center and down the sides. Encouraged by the success of this, I created something more akin to a Dahlia blossom, with petal-like elements. I then realized that since every petal was essentially a frame of an animation, their shapes could vary. So I made them quiver as they grew out from the center. I then continued to explore the animation potential of this new medium, experimenting with a variety of forms and transformations.

If you could watch an artichoke head develop, you would see its petals enlarge and move out from the center, eventually stopping when full size is achieved. Although a “Bloom” does not change size, its animation mirrors the growth of those artichoke leaves. But unlike the artichoke, the growth never stops.

I find it beautiful that spirals cannot be fully captured. They begin infinitely small and expand out, infinitely large. So, we’re only ever seeing a part of the spiral. You can’t actually see the whole thing—it’s all in your mind.

Obviously it’s visually spellbinding to watch—just from an aesthetic level. But what do you think of spirals and the bloom specifically? What do you think the appeal is on a metaphoric level?

Spirals combine what one might think of as two, contradictory world views: the historical Eastern worldview is one of recurrence and cycling as in reincarnation. The Western view is one of progress and growth and development. But the spiral encompasses both of these ideas very elegantly because the path is circling back on itself, repeatedly over and over and over again, and yet each time it comes around, it has progressed outward. It is both recurring and developing—a synthesis of these two, disparate ideas.

Given our desire for order and predictability in a disorderly and unpredictable world, it makes sense that we find a certain satisfaction in patterns. We like to dwell in “flow” [a term coined by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi to denote a feeling of energized focus]. The best way to be in flow is to be engaged in something that is actively increasing the complexity of the patterns in our mind.

Looking at a simple pattern might be interesting initially, but if it’s too simple, it doesn’t continue to engage us or keep us in flow. By designing patterns on the cutting edge of people’s intuition, you’re more likely to create something that captures and holds their interest.

That’s great. So, I guess my final question would be: What sort of advice you might have for someone that’s struggling to express their creativity?

If you want to be creative, you must foster your sense of curiosity. Be curious about your world—don’t just take things for granted or at face value. When you’re presented with something that you don’t understand, inquire. What’s going on there? Why is this doing that? Or why isn’t it doing something else? Of course, to be curious, you need to be observant. So, I guess I would suggest you first be observant and then be curious about what you are observing.

Curiosity is particularly important to me because it is the common thread and driving force behind my creative process. It’s the line that connects one piece to the next: I make something with a set of intentions, I poke and prod the result and note where it either meets or confounds my expectations, which raises questions, which provokes another idea, which leads to another attempt, which leads to more prodding, more unanticipated results, more questions, more attempts. And so on and so forth …

Written by Adam Rubin

Photos courtesy of John Edmark

To animate your own spiral, find this story and more in the pages of TANGRAM Volume Two.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.