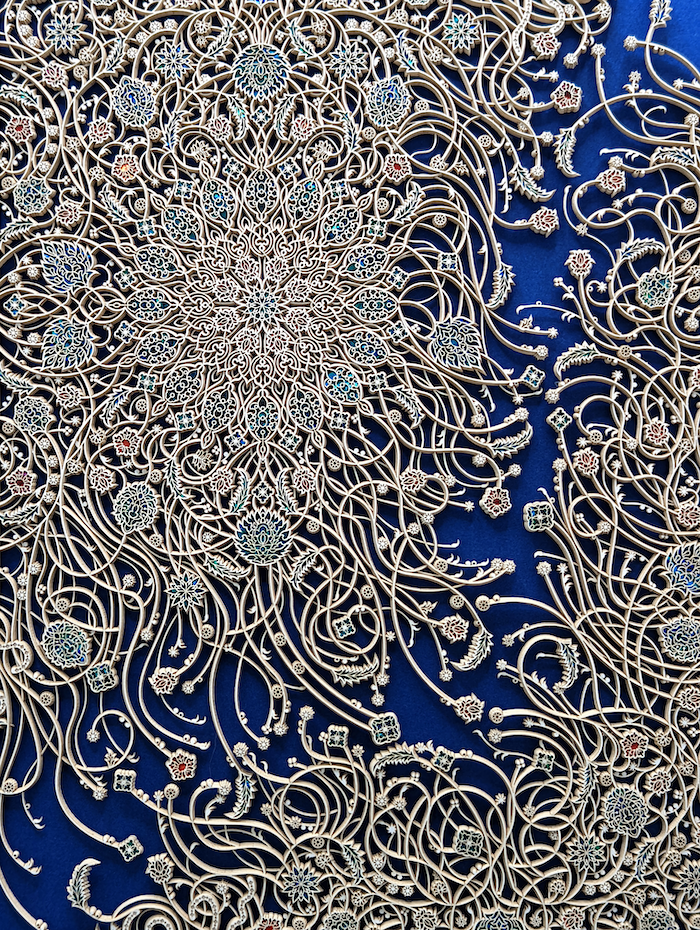

For centuries, the floral whorls and loops of Arabesque motifs have migrated and evolved. They are the fingerprints of the Islamic Golden Age—a biomorphic symbol for the unity of nature—patterns that touched so much of the world. The famous Persian designs found in the antique carpets of Kashan, Iran; the spiraling leaves draping Istanbul’s fragrant Grand Bazaar.

“They are like this visual language that’s being passed down,” says visual artist and designer Julia Ibbini. “The symmetry and the repetition. You get this beauty coming out of it.”

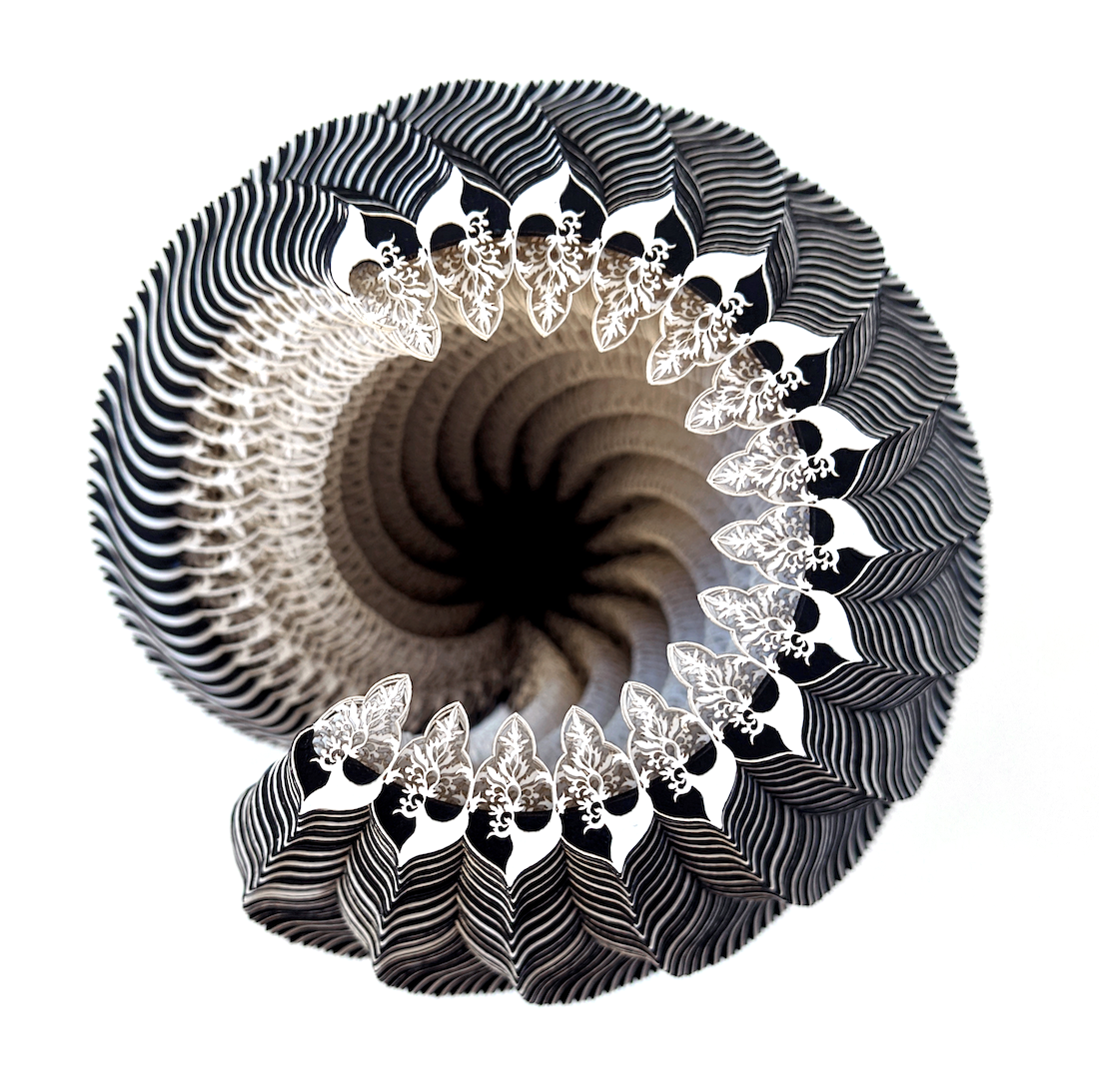

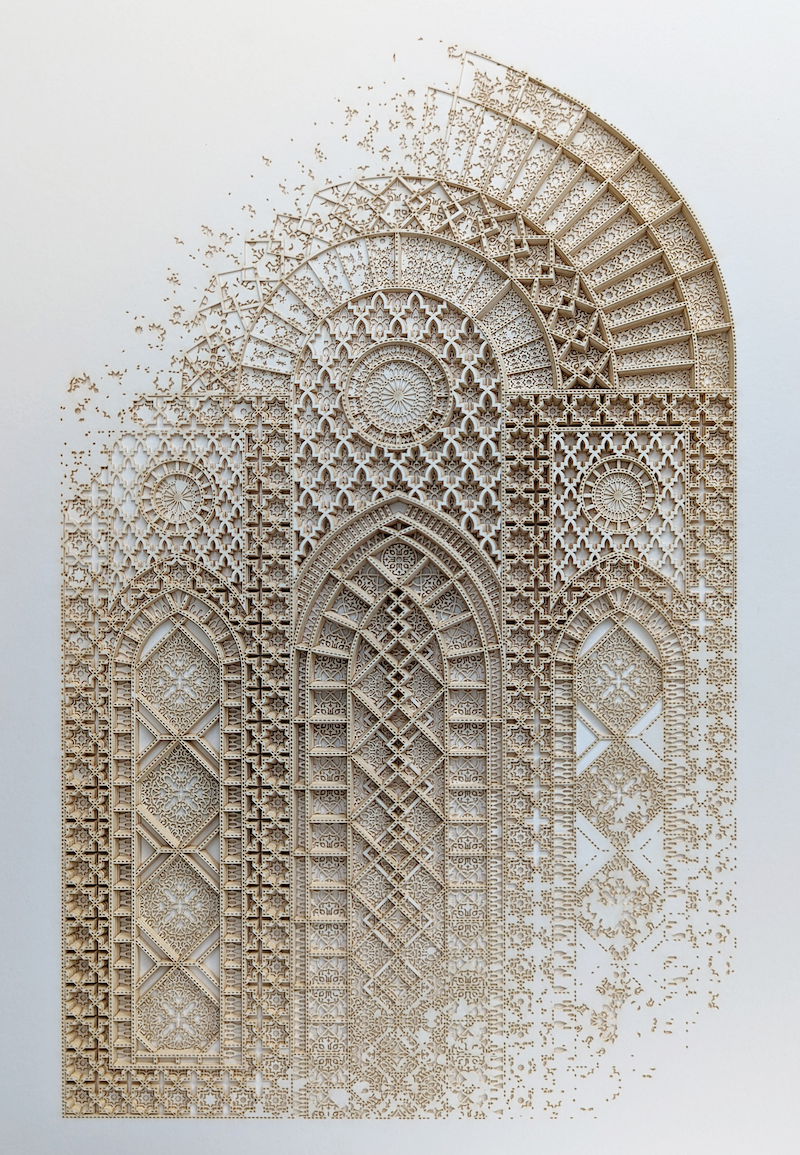

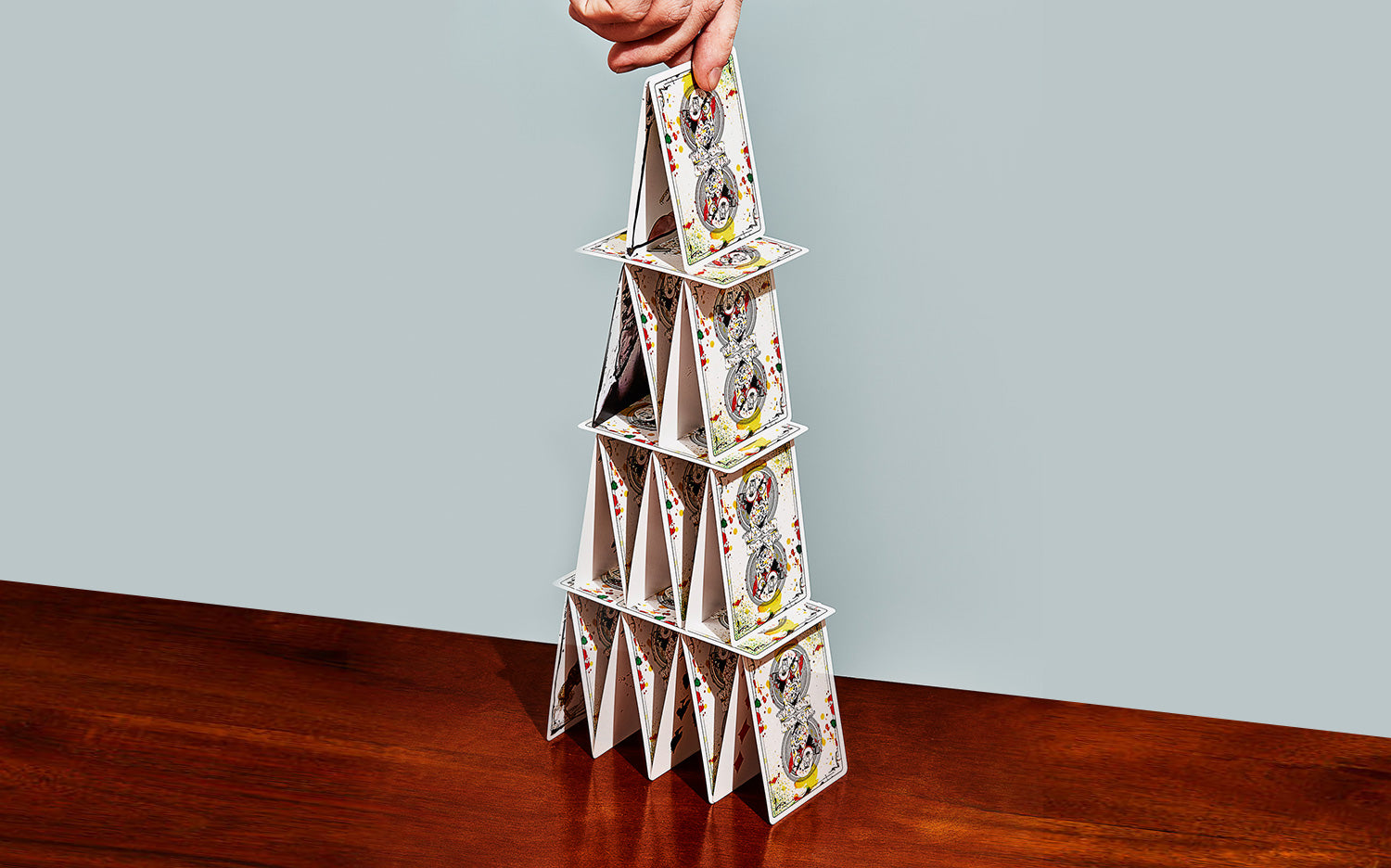

She and Stéphane Noyer, her husband and collaborator, have spent the past five years in their Abu Dhabi studio applying their own visual language to these ancient motifs by painstakingly crafting meticulous paper sculptures. The delicate motifs are sometimes composed of eight layers—some of which are broken up into a thousand tiny pieces—diligently assembled with a pin and glue. (Her vessel sculptures, which twist into sharp, organic shapes, sometimes have up to 350 layers of paper.) “People keep telling me I have a lot of patience,” she says, smiling.

For “Ornamental Mixtapes V3,” Ibbini began, as she does, with a digital sketch and reimagining various Arabesque motifs, with flowers and tendrils growing outwards. “The way I achieved that was almost like a glitch effect,” she says, explaining how she pulled the sweeping and sprouting motifs apart to create a collage of symmetries.

Next, the complex, curvy details are mapped out for the laser-cutting machine using a bit of computer wizardry. Noyer, a software engineer versed in computational geometry, fine tunes algorithms to cut motifs into paper without burning it. Using a mix of Adobe Illustrator and programming-language Python, he calculates how much distortion is needed within a curve so that the cut is smooth as though it were a straight line and the layers line up cleanly.

Even with such microscopic precision, Ibbini must balance a formula of power and speed for the laser cutter and experiment with paper types. “Sometimes it comes down to the length of the line you’re cutting at the time. So you play with the power within the cuts,” Ibbini says. Cutting one piece of paper can take as much as five hours to complete, which is a long time to wait for something to go wrong. “It’s a bit of a nervous dance around the machine,” she adds, laughing.

But the results of Studio Ibbini’s ornamental glitch motifs further expand the language of biomorphic art that evolved on ancient trade routes—worldwide influences obscured in interlacing patterns like reading tea leaves. A story altered subtly with age. “Where did they come from originally?” Ibbini asks with a shrug, “There’s no good way to tell.”

Find more of work from Studio Ibbini on Instagram @juliaibbini.

Words by David MacNeal

Images courtesy of Studio Ibbini

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.