Not many 10 year olds are capable of making a decision that charts their entire life’s course, but Jerry Slocum did. Through a mechanical puzzle he purchased with his allowance at a Chicago five-and-dime, Slocum’s destiny was revealed amidst the competing hobbies that defined boyhood in 1941.

“It was called ‘Rings “O” 7,’ which was Chinese in origin,” Slocum says. “It was much harder than any of the other puzzles I had bought before it.” Slocum discovered an algorithm to take apart and solve the tangled ring-and-wire puzzle two weeks later. “Nobody near me could figure it out—not my father, mother or sister,” he says. “Suddenly, I had this emerging capability to stand out in the local crowd.”

Even at age 90, Slocum still attracts a crowd. His popular claim to fame? Owning the world’s largest collection of more than 35,000 historical and modern mechanical puzzles. From 1986 to 2015, his puzzles were exhibited at 17 museums across the world, including the MIT Museum and Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry. That collector mentality has earned him international renown and appearances on TV and radio across North America, Europe, and Asia. He was most notably a guest on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson in 1986, Martha Stewart Living in 2002, and even served as a live TV guest in Mongolia in 2001 and 2004.

“I had quite a good time interacting with Johnny and Martha, having them try to solve some puzzles,” Slocum says. “Martha was so anxious to be able to solve them that in frustration she used some colorful language on air. The producer said they’d have to go back and do something about that in editing.”

Slocum was a diehard collector long before the Carson guest spot, having amassed 500 puzzles by his mid-teens. After earning his undergrad in mechanical engineering at the University of Illinois, he authored an article in 1955 for Science & Mechanics magazine that included a photo of him posing with his collection, which led to new connections that would further support his collecting habit.

Jerry & Margot Slocum with their puzzle collection for the October 1955 issue of Science & Mechanics magazine.

“I got letters from all over the world from that article, striking up friendships and correspondence with many other puzzle enthusiasts,” he says about the life-changing moment.

Slocum’s puzzles didn’t explode into world-renowned collection territory until around 1978 when he threw a little get-together among friends at his home in Beverly Hills. He called the gathering the International Puzzle Party because his nine friends represented three different countries. “The way I organized it, you had to be a puzzle collector with puzzles in order to be invited,” Slocum says. “Pretty soon, after a few years, we started to exchange puzzles. You would come with 50 puzzles all alike and you’d walk away with 50 puzzles that were all different. … It was a good way to start a puzzle collection.”

Before long, some serious changes were needed at the Slocum residence to accommodate the puzzles. “By 1984, my puzzle collection had overgrown my son Allan’s room and occupied quite a bit of additional space in our home,” he explains. “My wife, Margot, suggested that she would share her vegetable garden if I would move my puzzles to a new puzzle museum building in half of her garden space.”

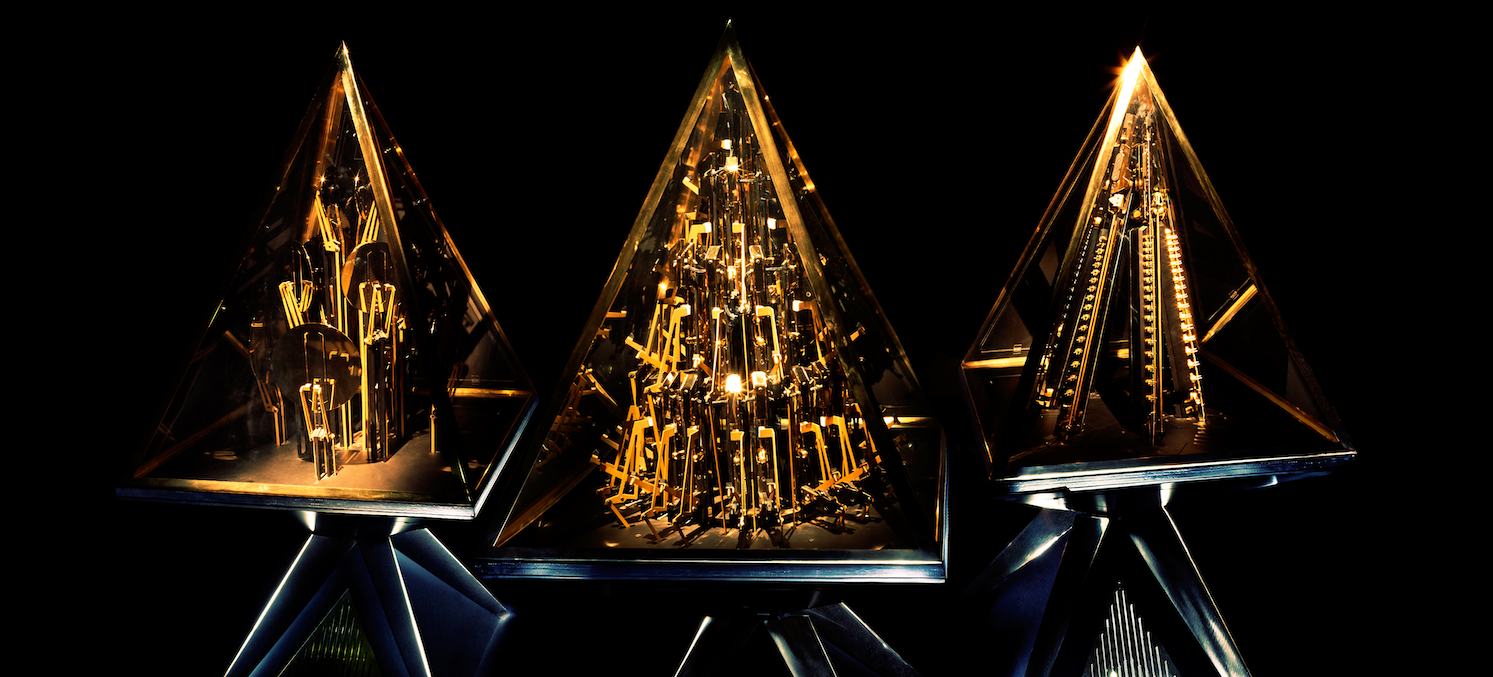

He was quickly emerging as the “World’s Greatest Puzzle Collector,” so Slocum didn’t just want to create a simple backyard museum. To gamify the actual building, he commissioned help from the great Japanese puzzle box maker and artisan, Akio Kamei.

“Akio invented and made for me three puzzle doors for my museum,” he says. “One is the entrance to the building, the second door opens my office downstairs, and the third opens the second floor door that opens up to all the puzzles on display.”

So, as a literal two-story museum was constructed in Slocum’s backyard—definitely not just a hobbyist’s shed—the International Puzzle Party outgrew Slocum’s living room. Fifty-five attended the party at a Los Angeles banquet hall in 1986. In recent years, attendance has swelled to over 400 people, with events hosted in the U.S., Europe, and Japan. The International Puzzle Party has been on hiatus during the Covid-19 pandemic with tentative plans to hopefully return this year.

Amassing tens of thousands of mechanical puzzles helped rocket Slocum to fame, but it hardly scratches the surface on his contributions to the puzzle community. As the author of 23 books, he’s documented the rise of the Rubik’s Cube, proven Napoleon Bonaparte’s interest in Chinese tangram dissection puzzles, and corrected a pivotal 19th-century historical record rooted in a lie obscuring the true inventor of one of the most famous novelty puzzles of the 19th and 20th centuries, the “15 Puzzle.”

Slocum was also influential in his day job as an aerospace engineer, credited with helping invent head-up display technology used in airplanes and fighter jets. “That technology is still in use in many modern airplanes, and was even put in a pace car for the Daytona 500,” he says.

The puzzle collection has become a monument to one man’s journey, and a legacy much larger than life. It includes more than 100 carved ivory puzzles from China, thousands of French, British, and American puzzles from the 19th century, and 4,000 books on puzzles and mathematical recreations dating to the 17th century, according to Slocum.

The emphasis is on creating great new puzzles, and that will continue forever.

To solidify popular interest in mechanical puzzles for generations to come, Slocum donated 30,000 puzzles from his collection to the Lilly Library at Indiana University in 2006. The collection is still growing. “In the Lilly Library, we have many puzzles that visitors can try to solve,” he says. “We have a booklet with each puzzle that shows the starting positions and instructions of what the goal is. And we have several pages of hints that help the solver solve the puzzle; and then on the last page we show the solution so solvers do not feel that they failed, so they can get better and better at solving puzzles.”

The Slocum Puzzle Room at the Lilly Library

Slocum is not done leaving his mark on the puzzle world. A few years ago, his son, Allan, took the reins as CEO of the Slocum Puzzle Foundation. But even at 90, Slocum shows no signs of slowing down. Living up to the designation as the “World’s Greatest Puzzle Collector,” he has embarked on a new obsession: investigating the origins of mechanical puzzles.

The search has involved treasure-hunting in museums across Europe, China, and Japan; and he’s since uncovered and documented at least 156 bronze rings used as intricate padlocks to secure hefty coin bags and purses in 1st century ancient Rome. (He’s purchased at least 30 of these rings for his own collection.) He’s also discovered that the oldest versions of these moneybag rings date as far back as 200 BCE in ancient Celtic regions.

Visions of past marvels and revelations point at the future of puzzles. As mechanical puzzles evolve into an era where 3D printers can manufacture complex plastic pieces with great precision from digital designs, Slocum foresees what is in store for the industry. “The emphasis is on creating great new puzzles,” he says, “and that will continue forever.”

Words by Anthony Bowe

Photos by Matthew Roharik

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.